Sir, do you believe in fate? ──The future of Hong Kong legend

The cession of Hong Kong Island actually involved a lot of mistakes and even confusion.

Author: GUDORDI | 2022-10-18

A somewhat confused war more than 150 years ago brought Hong Kong to the center stage of Chinese and world history. (Wikimedia Commons)

Continuing from the above: “My heart is like a small wooden boat…”

Zhang Zai asked Shao Kangjie (author of “Huangji Jingshi Shu”): “Sir, do you believe in fate?”

Shao Kangjie replied: “If it is destiny, you will know it. But if the world calls it destiny, you will not know it. ” 』

In the last chapter, the author pointed out two points, which showed that the cession of Hong Kong Island actually involved a lot of mistakes and even confusion. It is worth noting that Lin Zexu summoned the merchants of the Thirteenth Bank on March 18, 1839, and asked them to order foreign merchants to hand over all opium within three days and sign a recognizance letter stating that they would no longer sell opium. Otherwise, “Once If all the goods are found and no official is found, the person will be punished and he will be willing to admit his guilt.”

Then, Lin Zexu publicly burned cigarettes in Humen on June 3, 1839, but the Treaty of Nanjing was signed on August 29, 1842. Therefore, the entire Opium War spanned three years, during which many things and turning points occurred. Upon closer inspection, I believe many people will agree that the development of the whole thing is full of twists and turns, enough to make a fascinating movie.

A battle that neither side really wants to fight.

It is worth noting that the development of the whole thing is quite open-ended in many places. The personalities and judgments of several main characters seem to have a key influence on the evolution and final outcome of the matter. Looking back today, we can’t help but ask, if the handling and judgment of several key figures at that time were not like that, would this battle not have happened? This also extends to the third point I want to make, which is that in this war, neither side seems to really want to fight; even if it must be fought, the Qing Dynasty may not be defeated; even if the Qing Dynasty is destined to be defeated, it may not be Land must be ceded; even if land must be ceded, it does not necessarily mean Hong Kong must be ceded.

According to records, Lin Zexu judged at the time that Britain would not mobilize troops to fight this war all the way. He also wrote a letter to Queen Victoria to avoid a war as much as possible, but this letter should never have been delivered to the Queen. What exists are only copies. It is worth noting that the Suez Canal was only opened in 1869, so in 1840, it was necessary to bypass the Cape of Good Hope in South Africa before traveling from Britain to the Far East. Therefore, to the British government, China is really a far, far away place. For individual British businessmen, the profits from opium may be considerable, but relative to the fiscal revenue of the entire country, it may not really be a big deal.

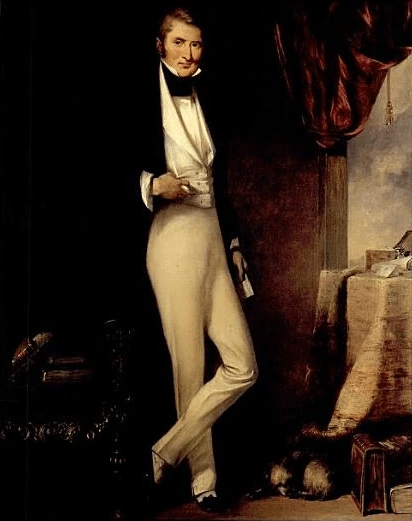

Looking back today, the biggest driving force for Britain to send troops that day should have come from British businessmen in China at that time, especially Dr. William Jardine (1784-1843) of Jardine Matheson and Landshirok of Poshun Matheson. ·Lancelot Dent (1799-1853). Jardine’s William Jardine even traveled a long distance back to China to lobby in the House of Commons. According to the archives, the lobbying strategy of a group of British businessmen at that time was to low-key deal with the opium content of the entire incident and focus on trade, Lin Zexu’s tough handling methods and unreasonable thirteen-line system.

William Jardine of Jardine & Co. (Wikimedia Commons)

Britain's decision to send troops was not a one-sided decision

In any case, between 1839 and 1840, many pamphlets of unknown origin appeared in the UK, which mainly complained about the Thirteenth Line Blockade incident and falsely accused Lin Zexu of planting opium poppies privately. The purpose of the ban on smoking was only for personal gain, thus arousing a certain degree of resentment in British society. Public outrage. On September 30, 1839, 39 companies and manufacturers in the British textile industry city of Manchester jointly sent a letter to British Foreign Secretary Palmerston, saying that China’s smoking ban was an “act of aggression” against Britain and “hope that the government can take advantage of this opportunity.” “To put China’s trade on a safe, solid and permanent basis.” On October 1, 1839, the British government held a cabinet meeting and finally made the decision to “send a fleet to the China Sea.”

But despite this, the British government and opposition parties were still hesitant about sending troops to launch a war. On April 7, 1840, the opposition Conservative Party proposed a motion in the House of Commons to veto the decision to send a British fleet to China. After three days of heated debate, the House of Commons finally rejected the motion by 271 votes to 262. This shows that Britain’s decision to send troops was not a one-sided decision. Theoretically, as long as 5 to 10 members of the House of Commons change their stance at that time, the war may not be fought. Even if the two sides appear, a war will eventually break out, and the consequences will not necessarily involve the cession of Hong Kong.

It is worth noting that according to files, British Foreign Secretary Palmerston and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs have not been too enthusiastic about taking over Hong Kong Island. According to records, after Yi Lu was deposed, the British proposed to open more ports in exchange for ceding Hong Kong Island and stopping the war. If the Qing government accepted the proposal and opened more ports, Hong Kong might be returned. Therefore, the cession of Hong Kong , there are indeed many accidental and unexpected elements.

British Foreign Secretary Palmerston. (Wikimedia Commons)

Pure chance or forces beyond the immediate?

Looking back at the past 5,000 years of Chinese cultural history, we can say that Hong Kong did not play an important role in the first 4,800 years. But a somewhat confused war more than 150 years ago brought Hong Kong to the center stage of Chinese and world history. Is this purely an accident of history, or is there some power beyond the immediate that has taken a fancy to a small place like Hong Kong? How can we bring it into the center of the stage of Chinese and world history? In the next chapter, the author will further explore this issue.

“Hong Kong’s Legendary Future” Series 6

Contact the author: Gudordi@proton.me